On a Great Discovery by the Father of a Minor Publisher of Middlemarch

And so Sebald stopped writing and began sitting all day at the picnic table outside his apartment to smoke cigarettes and, together with his plane fixers, ponder the category of birds-nest.

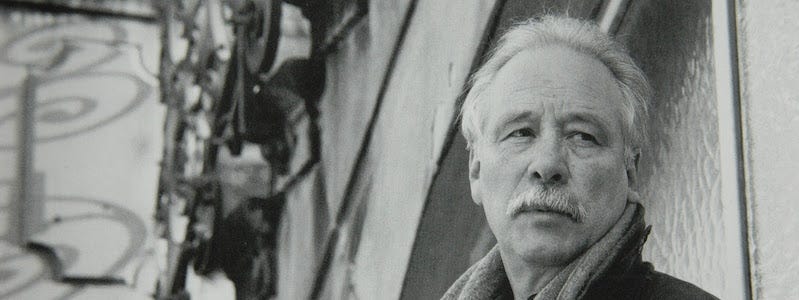

W.G. Sebald faked his death in order to get the peace and quiet to write a dictionary. He planned to produce an English-German dictionary that read as if it were composed by a group of German aviation mechanics who, late in life, devoted themselves, respectively, to the study of English literature, the reconstruction of Aristotle’s lost dialogues, and solving the riddle of the 19th Century.1 He completed A but got stuck in B on the entry for bird’s-nest when the Aristotelian mechanic pointed out that a bird’s-nest lies outside Aristotle’s categories2 of nature and art. By the strict rules of the dictionary, it cannot be defined until its proper category is discovered.3

And so Sebald stopped writing and began sitting all day at the picnic table outside his apartment to smoke cigarettes and, together with his plane fixers, ponder the category of birds-nest.

It was there at the picnic table that he met his neighbor Christopher McCaffery, insurance adjuster, father, and amateur orthographologist. McCaffery spent his spare time searching for “the foundational logic of spelling” and the relationship between that logic and “the ground of grammar,” but like many scientists he found something altogether different than what he initially set out to find. In the notes and diagrams in the margins of the manuscript of Wilhelm Schubart’s unpublished treatise Die Rechtschreibung, Christopher McCaffery made his Great Discovery: the true nature of literature. He discovered that literature is not a series of discrete creative acts or a history of works and influences and relationships. Literature is a finite set of tasks. André Breton was wrong to say “After centuries of philosophy, we're still living off the poetic ideas of the first men.” Those first men completed the first poetic tasks. That’s all. Every writer completes the task set before him, and one day all the tasks will be complete. And then literature will be done, and man can begin something new.4 Or the world will end.5

Sebald and McCaffery sat and smoked and spoke about the Discovery until nightfall and then returned to their desks. The solution to the birds-nest problem did not present itself that night—and despite daily labors since, has still not presented itself—but, in the light of the Discovery, Sebald understands finally the gravity of his task. In the morning he gets up from bed and walks to his desk. The mechanics whisper, “The madman cometh!” He sharpens his pencil. He polishes the buttons.

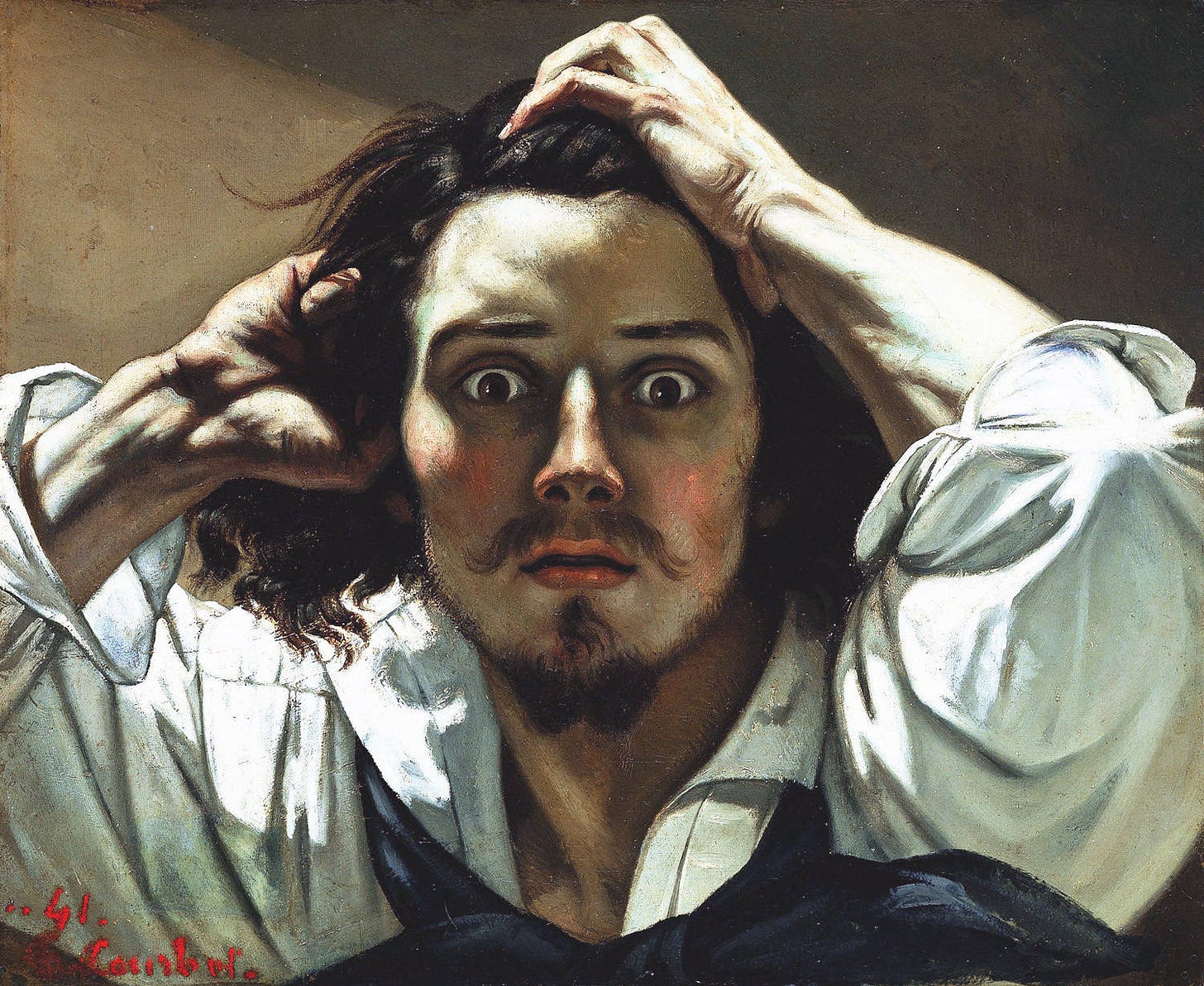

I.e., the riddle of the unevenness of Gustave Courbet.

To search for the proper category of a thing is to search for an aspect of its being, which is why Darwin understood himself to be an ontologist. Categories, on the surface either arbitrary or reasoned ideas of order imposed on things, turn out to be at the heart of things themselves. Sebald’s dictionary, by posing the question of categories, makes lexicology into an experiment in the science of being. An experiment to which we are or were unwitting observers and participants.

The one time Sebald and I talked on the phone, he told me several times, “Never argue with a German aviation mechanic.” At the time of the conversation I knew nothing of his dictionary and so could make no sense of the admonition. But I learned the wisdom of the warning on a recent trip to Gelsenkirchen. Your lesson awaits you. Do not forget!

Christopher McCaffery’s son, Chris McCaffery, labors at completing the literary tasks assigned to him by his father: the creation of a “review of books” named for every city and the production of multi-volume editions of Large Books. Chris’s multi-volume edition of Middlemarch ( “Liddlemarch”) brings us closer to the completion of literature than he knows. As the late Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson would say, "Stand ready to greet Moshiach: Everything is already prepared, all that remains is to polish the buttons."

Cf. the frontispiece of Bacon’s Novum Organum.