The Decline of the West

“The infinite does not transcend the finite,” says Hegel. “Rather, it is the very movement of the finite itself.”

The arrest of Daniela Klette after her thirty years underground in the infamous third generation of the Red Army Faction brings to mind the work of Captain Gerald Grable, commander of the secretive Army company tasked with monitoring left-wing terrorism in Europe in the 1980s and 1990s. Grable pioneered what came to be known in the inner circles of DOD as “theologico-political intelligence analysis.” In studying left-wing terrorism, he and his men accidentally discovered the Heart of the Tragedy of the West and the Logic of Dissolution, an achievement only recently acknowledged in the Department.

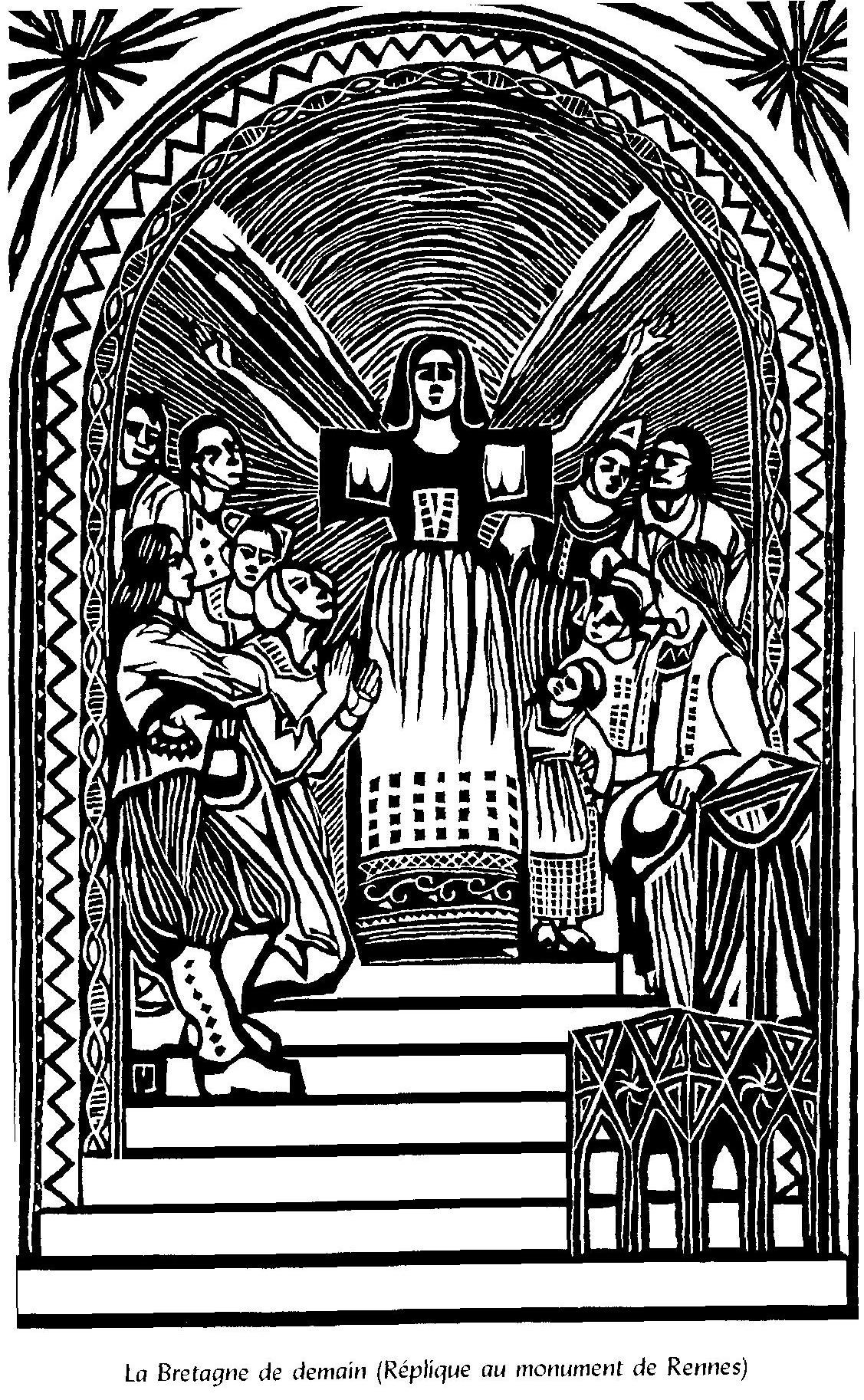

The Captain’s daughter, Lena White Grable, was born in Athens, Ohio but raised mostly in Grafenwöhr, Bavaria. She did not do well or poorly in school and learned to speak and read German. She barely knew her father, who distinguished himself as an officer for the fastidiousness of his reports and spent as much time as possible away from the family. Her mother had an enthusiasm for minor European nationalisms, so the house was filled with prints by Jeanne Malivel and Basque propaganda posters and the folk songs of Brittany and Corsica and Euskal Herria.

When Lena reached the age of majority, she left Germany and her mother and father at the first opportunity and moved to Bartow, Florida to share an apartment with her cousin Leanne. Not having a better plan, she registered for cosmetology school.

Before she boarded the plane for Florida, Lena’s mother made her promise that she would keep up her German. Lena agreed, and, as usual, she kept her word. So after the second week of learning everything there is to know about hair and makeup, she went to the Bartow, Florida public library to find a book in German.

The Bartow library is unique among the libraries of small American cities in that it maintains large book collections in French and German, with an emphasis on modern theology, drama, and medieval poetry. All thanks to a bequest by local barber, magician, and lottery winner Carlos Álvarez, whose passion for German and French and the Nouvelle théologie knew no bounds.1

Lena arrived at the library expecting to find one or two books in German, only to be ushered into a whole room of them. She pulled at random from the shelf a small paperback edition of Hans Urs von Balthasar and Adrienne von Speyr’s essay Die Tragödie der westlichen Kirche.

A lot of things fell into place when she read that essay: her father’s work, her mother’s collecting habits, the stench of cultural death everywhere and covering everything. She remembered the night she returned home with her mother from a conference on the Corsican nationalist poets Paoli, Ottavi, Quilici, and Nivaggioni. Her dad was in the kitchen with the lights off whispering to himself a poem in German:

Wenn im Unendlichen dasselbe Sich wiederholend ewig fliesst, Das tausendfältige Gewölbe Sich kräftig ineinander schliesst; Strömt Lebenslust aus allen Dingen, Dem kleinsten wie dem grössten Stern, Und alles Drängen, alles Ringen Ist ewige Ruh in Gott dem Herrn.

She learned later these lines from Goethe that begin Spengler’s masterpiece, but in the kitchen that evening she knew nothing about Goethe or Spengler. Her dad’s posture and actions, so abnormal for him, frightened her, but he beckoned her closer and pulled her into a hug and continued to whisper the poem. Her fear turned to contentment and peace, and she stayed in her father’s arms for a long time.

The Heart of the Tragedy of the West and the Logic of Dissolution, once understood and believed, tend to make men go mad, so von Balthasar and his mystical friend attempt in Die Tragödie der westlichen Kirche simultaneously to explain the World Situation and inoculate readers against the madness attendant to understanding that Situation.

Captain Grable and von Balthasar understood the World Situation in much the same way but drew different conclusions from that understanding. It’s clear both men felt a great responsibility in their uncovering the Heart of the Tragedy; like they were tasked with holding back an oncoming tide. What sort of tide? Something akin to what Freud called “the black tide of occultist mud.”

After she read the Balthasar essay and Figured Things Out, Lena wrote a letter to her father. Most of the letter consisted of anodyne updates about her cousin and cosmetology school, but it ended with a postscript in German about the life-world (umwelt) of understanding and the necessity of self-concealment and the unfolding of the Final Finality.

“The infinite does not transcend the finite,” says Hegel. “Rather, it is the very movement of the finite itself.” How was Daniella Klette underground for so long without being captured? How did her generation of the RAF operate after the disappearance of its state sponsor?

From the first department store bombings by Andreas Baader and Gudrun Ensslin in 1968 to the final RAF communiqué in 1998, German left-wing terrorists have told each other the same riddle. György Lukács advised, in case you get picked up by the NKVD, to carry two razors. One razor for shaving; the other for slitting your wrists. The riddle is: why can’t you shave and slit your wrists with the same razor?

Whenever the Verfassungsschutz allowed Captain Gerald Grable to interrogate an arrested terrorist, he would ask first how the prisoner answered the riddle. But no matter how many times he asked the question, he could never answer the riddle himself. That is, until he got Lena’s letter.

Among the great pleasures of this world is a week of prodigious inactivity in the company of his diaries! Álvarez read literature with the attention of a widower trying to recall a childhood memory at the grave of his mother. His donation to the library stemmed from exuberant love for the French and German languages and literature, not altruism or love of place.