Margaret Valéry, Ethnologist

Her passion for ethnology didn’t sway her father, who refused to let her travel to north Ciscaucasia, so she waited and read and dreamt of walking trees.

“Oh hell, Maggie, why do you want to take photographs of these Kitdjick people? In what godforsaken place?”

—”The Kijk people, daddy, in Ciscaucasia.”

“Kitdjick, Kijick, Kijk. I’ve never heard of them. Nobody’s ever heard of them. They’re not in our Encyclopedia! Grandpa’s never heard of them! And where in the world is Ciscaucasia? You’re just a girl for God’s sake!”

So went the oft-repeated suppertime conversation between Margaret Valéry and her father Orson1 after the teenage Margaret discovered Elman Service’s Profile in Primitive Culture and decided to become an ethnologist. With her heart set on a life of ethnology she abandoned the typical reading habits of a teenage girl in 1950s Cincinnati in favor of reading every work of ethnology and ethnography she could find, and learning whatever languages she needed to learn in order to read them. And thus she discovered the Kijk people in the ethnographic notebooks of Luis Lezama Leguizamón Sagarminaga, whose studies of Kijk courtship and burial rituals are unrivaled in length and detail. Her interest in documenting Kijk customs evolved from a desire to an obsession after translating Baron Julius Evola’s Saggi sull'idealismo magico.

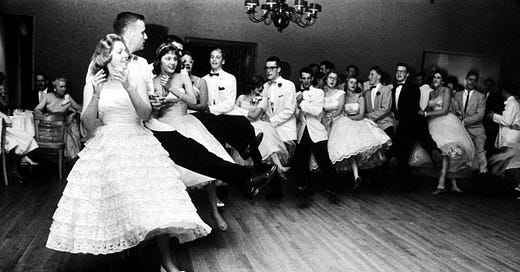

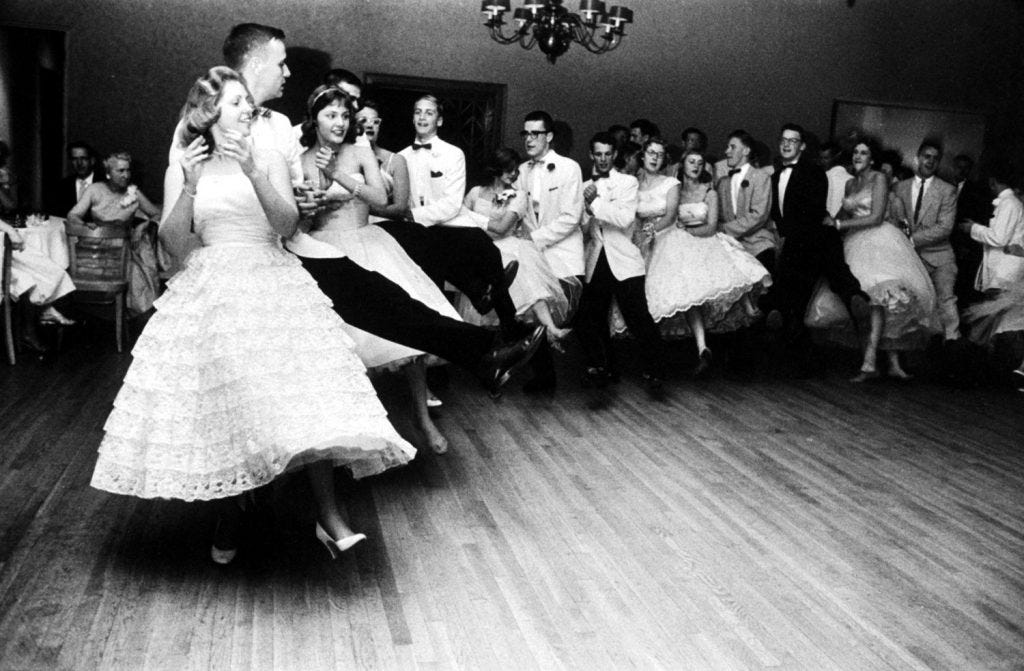

But her passion for ethnology didn’t sway her father, who refused to let her travel to north Ciscaucasia, so she waited and read and dreamt of walking trees. Nor did her aspiration make her po-faced or boring. She was a good dancer and quick to laughter. Four boys asked her to prom, and she said yes to the last one, Brian George, handsome and mischievous son of a Proctor and Gamble man. He fell in love with her and told her so. The parents assumed they’d marry and yet were surprised speechless when the couple eloped without warning or invitation and took a bus to New York, whence a ship to Europe.

Mr. and Mrs. Brian George were headed to Ciscaucasia. For the first three months of their journey, they sent their parents weekly postcards and a handful of longer letters.2 Then the postcards and letters stopped coming, and the parents’ attempts to find them came to nought. The paper trail goes cold until the 1967 publication of Hombres olvidados, Montaña escondida by a small Carlist publisher in Madrid. The author is called Margaret Lezama de Córdoba y Sanz, and the style of the Spanish indicates she is not a native speaker. Most of Hombres olvidados chronicles the author’s time with the Kijk people, and the death of her first husband in a duel. It closes with an argument in favor of Catholic monarchy, an argument that appears at first to be a non sequitur but slowly reveals itself to be a retelling, by obscure analogy, of the history of the Kijk people from the beginning of the world to the death of her first husband, whose death takes on the structure of an apocalypse.3 The author is almost certainly Margaret George née Valéry.

At the start of each repetition of The Ethnology Argument, her mother Janet would retreat to the kitchen to busy herself with something, anything loud enough to cover the sound of the talking. Janet was no shrinking violet, but the thought of her daughter traipsing about the Caucasus mountains filled her terror.

Preserved in the private library of the Ohio Valley Friends of Evola, an organization more inclined to amateur ornithology and Dante translation than Fascism. We gained access to the library’s ethnography archives thanks only to the patient entreaties of Louis Toransky, of blessed memory.

Or worse.